The Savings Glut, Trade Wars, and a Broader Definition of Global Liquidity, Part 1

Contrary to popular belief, U.S. exports are actually up because the dollar has been in long-term decline..

I watched Maurice Obstfeld’s fascinating recent lecture at the Richmond Fed with great interest. He’s not a household name I’d expect you to know, but he’s a smart dude who spent time with the IMF, Bank of Japan, and the White House.

In the lecture he revisits Bernanke’s 2005 “global savings glut” because he thinks its playing a misguided role in 2025 White House economic policy.

In this first post, I’m going to explain just what Obstfeld thinks about the savings glut and the U.S. trade deficit with China.

But in part 2, I’m going to bring in perspective from the research department at Salomon Brothers investment bank from the 1980s. This is Henry Kaufman and Mike Howell who’ve beaten the market for years on the premise that macroeconomists don’t really understand the way that global liquidity effects the “real economy.” Just to tease a bit: there is WAY more footloose capital in world markets driving asset prices (e.g. real estate, stocks, Bitcoin), domestic interest rates, and exchange rates than is commonly believed.

There will be a part 3 where I take their practical business perspective and apply it to the history of the world economy in the past four decades.

The global savings glut is probably more complicated but here’s a “long story short” version. Riding the back of Asian growth in the 80s/90s and OPEC oil prices, a bunch of foreign entities made enormous profits. There was so much profit that it outstripped available opportunities to reinvest it into capital inputs (machinery, research and development, land, new marketing strategies, or anything that might lead to productive output and sales growth). So corporations and such just had way more “savings” than investments. The effect of this, so Bernanke claimed, was to drive down interest rates all over the world. With more money just sitting around there is less demand for new financing (credit/money) and therefore the entities that lend new financing need to offer it at a lower price. It’s really not that complicated: central banks were willing to lend out money to potential borrowers with lower interest payments because demand for it was lower.

Two consequences of lower interest are surmised in this story. First, loose monetary policy allowed more and cheaper credit available, which pushed investors to take bigger risks. This drove enormous demand for assets, pushing up equities (stocks) and real estate prices. Many have linked this savings glut story to the outsized valuations that burst in the 2008 global financial crisis.

The second consequence, which matters a lot to Trump and friends, is that all that savings leads to a stronger U.S. dollar which has made U.S. exports less competitive. With less competitive exports means a declining manufacturing base and a loss of “good jobs” in middle America. The logic is that those global savings don’t just sit in bank accounts, the entities that have them need to invest them in financial products/assets that will hold their value over time. Most of those products are denominated in U.S. dollars and that creates an extreme demand for the greenback. With the value of the dollar up, manufactured goods from elsewhere become more attractive to global consumers because they are sold in cheaper currency. You can see this consensus emerging in Washington circa 2023 in Gordon Hanson’s Foreign Affairs piece. It’s all linked to Chinese unfair trade practices and this is why vice president V.P. Vance believes we need to devalue the dollar.

You have to ignore the chicken and the egg problem (there are savings because of Asia’s rise as producer of the world, not the reverse), but you can see the logic: the idea is if we place tariffs on the U.S. imports from China this will drop their harmful savings, the U.S. dollar will fall, the U.S. will get to increase its exports and reduce its trade deficit. The moral background to it (because there always is one) is that Asian producers shouldn’t get to profit off of U.S. consumers without paying a price.

Obstfeld’s lecture points out that there are empirical problems with this “savings glut to trade war” story. The problems he points out are about the timing of historical trends; i.e. when exactly did interest interest rates, exchange rates, and savings actually change direction. The timing is off, which he implies means that the overall structural features of the story still do have some legs. He points out five problems:

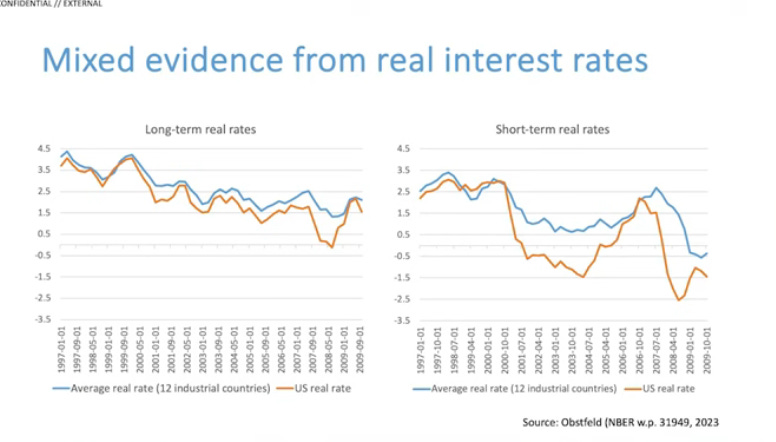

There is no sharp drop in interest rates. Interest rates in the OECD were low after the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 (which is thought to cause the big savings glut in Asia). Moreover, Obstfeld points out that U.S. real rates were way lower than OECD averages throughout this period as well and even had a rise in the lead up to the Great Financial Crisis. The implication of this is that a savings glut didn’t cause interest rates to fall because they were always low. See below:

Global savings actually do not rapidly increase after the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. Foreign exchange reserve stocks by emerging markets was more impressive. But both really don’t take off until later. See global savings below.

The dollar is actually falling in the middle of the 2000s! You can see that below. the implication is, the dollar is falling at the exact time that global savings glut is supposed to be pushing it up in the lead up to the Great Financial Crisis of 2008.

You can see the long term decline below and the policy regimes that gave important, temporary boosts (more on those in part 3).

Relatedly, because the dollar is falling in the mid-2000s, U.S. exports actually go up during the 2000s and beyond! See below. This really puts a monkey in the wrench because a stronger U.S. dollar’s connection to less competitive U.S. exports are what’s behind the idea that a trade war can bring back good jobs to middle America.

Another puzzle Obstfeld points out is that import prices into the U.S. are also falling in the 2000s. So this really creates a problem for the trade deficit/global savings glut story. The dollar is falling and U.S. exports are growing AND import prices are RISING. And yet the trade deficit continues to grow: the U.S. still imports way more than it exports despite the fact that exports are getting cheaper and imports getting more expensive. The biggest increase to the U.S. trade deficit occurs exactly when the dollar is falling. Weird right? See below:

The basic puzzle is: how can a global savings glut contribute to U.S. manufacturing decline if the dollar is falling during this period, interest rates were always pretty low, and import prices are actually rising and U.S. exports are getting better. Wild.

So how does Obstfeld square this?

He doesn’t say it like this but his answer, more or less, is that U.S. public and private financial institutions created an enormous amount of credit in the 2000s. The way to talk about this in polite company is to say “debt issuance.” Interest rates were kept low (loose policy) and corporate debt was cheap. All to stimulate the economy.

On the one hand, this had the effect of allowing U.S. citizens to have credit cards, auto loans, and much more to buy way more imports than the exports the U.S. was creating. This explains why the trade deficit was growing even as U.S. exports were increasing as a result of a falling dollar.

On the other hand, it had the effect of pulling foreign liquidity into the United States which led to the declining U.S. dollar. There was so much cheap U.S. debt (i.e. new money) being created that it far outstripped the demand for dollar assets in the world. If the reverse had happened and demand for dollar assets outstripped its supply than the dollar would rise in value (which is kind of the situation we got after the Great Financial Crisis).

That’s a little confusing if you aren’t familiar with this stuff. It wasn’t intuitive for me. So I like to imagine it in these steps:

U.S.’s central bank, retail banks, non-bank financial institutions, and corporations can take out debt by selling bonds or repos to someone else. That means selling an agreement to pay back the amount with interest. They do that at a certain price (the interest rate) which makes purchasing that debt more or less attractive. Those institution take the credits they generate from the selling of that debt and use it as collateral to create more credit in the U.S. economy, which is what you and I get access too.

That normal, but what changed was that 1) the rules (I think in the 80s?) on how much collateral was needed for a financial institutions to create credit were loosened, so you need just 1% collateral in some cases when it used to be 20% collateral; and 2) buyers emerged in the world economy who could afford to purchase U.S. debt. The first allowed our society to artificially enjoy a one-time increase to the “money multiplier” (the amount of credit that could be created from cash). And the second meant that so long as there was someone willing to buy it out there in the world, U.S. financial institutions could keep creating credit.

Wait… why would someone in the world want to buy U.S. debt? Isn’t debt like a bad thing? Well the answer is two fold. First, if you are in Asia and just purchased debt from a U.S. financial institution that means the U.S. institution is going to be paying you interest for it.

But, more importantly, you get to use U.S. debt as collateral to create your own money and credit in your home market.

That’s right. U.S. debt is viewed as an asset elsewhere in the world that allows foreign entities to do their own money multiplying debt creation. The reason this is possible is because U.S. debt is viewed as a “safe” investment that is assured to keep paying out in the long term and even if there is some crisis in the global economy. It’s better to buy U.S. debt than it is to invest your profits into their own domestic investment projects (that have a dubious return on investment).

But why would the U.S. financial institution sell away debt that it will now have to pay interest on? The answer is because that interest will be lower than the interest they are charging the U.S. consumer or company to use that money. So the interest the bank is paying to a foreign buyer is cheaper than the interest they are charging you for your student loan. They profit from the difference and higher quantities of it means more profits. U.S. citizens benefit because they have more money to buy stuff with. Its not as simple as this three-step chain (u.s. bank, foreign buyer, u.s. consumer); there are long chains of intermediaries that expand global capital all over the world.

So Obstfeld thinks the U.S. was throwing lobs of debt onto the world and this caused the dollar to depreciate in the mid-2000s. This depreciation allowed U.S. exports to be sold at lower prices and therefore pushed U.S. exports to increase. But the trade balance didn’t reverse because all that debt was used by U.S. consumers to buy way more imports. In turn, savings in other parts of the world was used to fund this credit bonanza. So for him, simply putting tariffs on imports is not going to reverse this situation. He surmises that trade policy doesn’t have an effect on exchange rates. And interest rates do not anatomically balance savings and investment rates between two nations.

In fact, he points out, interest rates are related to broader factors. The most important of these are balance sheet constraints of investors, their risk appetize, and what are called “gross capital flows.”

He leaves this last part vague. And there is where we will need to bring in the Salomon Brothers investment bank diaspora and the great book “Capital Wars” written by Mike Howell. Please see part two!